Documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras. Photo: Frazer Harrison/Getty

Laura Poitras may be best known as an Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker, but she identifies equally as a journalist: “I believe that documentary filmmakers who are taking on state power, we are doing journalism, and we also need the protections that journalists have, right?” In the “terrifying” era of Donald Trump’s presidency, she says, institutions to protect journalists are needed more than ever.

So it’s fitting that Poitras’s latest film, the riveting Cover-Up, which just this week was shortlisted for an Oscar, makes a matter-of-fact case for the vital role of journalists throughout world history by focusing on one trailblazing reporter in particular: 88-year-old Seymour “Sy” Hersh, who received a Pulitzer in 1970 for his revelatory investigations into the Vietnam War and the My Lai massacre, and who has since been a vital voice on stories from the Watergate scandal to the Gulf war to the killing of Osama bin Laden.

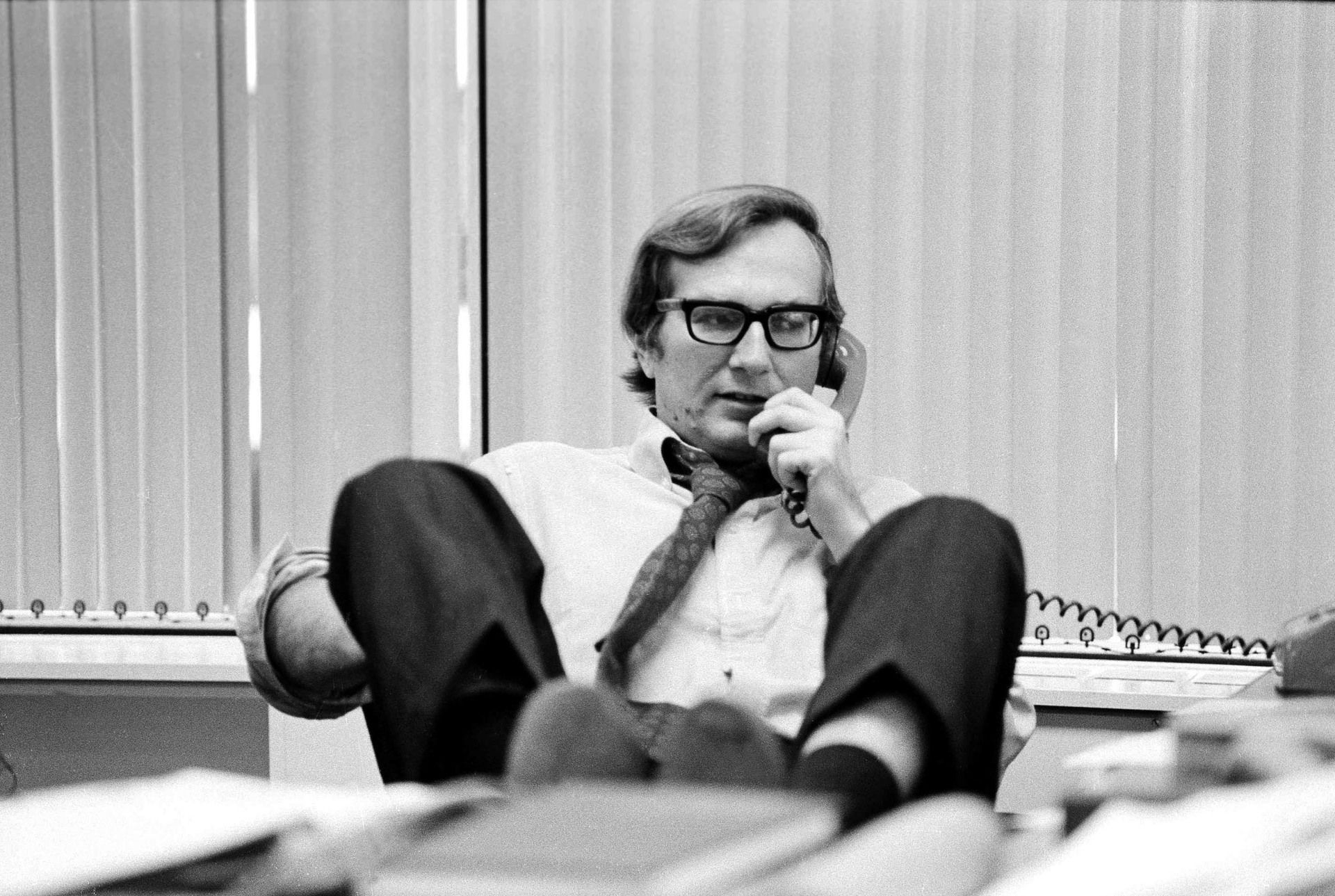

Seymour Hersh in the Washington bureau of the New York Times in 1975.

As a portrait of an individual speaking truth to power, Cover-Up, which Poitras has co-directed with Mark Obenhaus, fits alongside a number of similarly impassioned and justice-minded films in her oeuvre. These include 2014’s Citizenfour, a firsthand examination of Edward Snowden and the NSA spying scandal that won her an Academy Award, and 2022’s All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, about photographer Nan Goldin and her campaign to hold the Sackler family to account for their role in the US opioid epidemic, for which Poitras won the Golden Lion for best film at the Venice Film Festival. Born in Boston, Poitras initially pursued a career as a chef, before enrolling at the San Francisco Art Institute and discovering a greater passion for filmmaking.

Sy Hersh is the latest of several fascinating human subjects in your films, following the likes of Julian Assange, Nan Goldin and Edward Snowden. What draws you to them?

I don’t think of them as subjects so much as protagonists. And I'm really compelled by outsiders, rebels, troublemakers: protagonists who are confronting power, and are willing to risk so much to expose wrongdoing, but who are doing it to shed light on systemic problems. Mostly it's been about US government state power, but All the Beauty and the Bloodshed was about corporate power and wrongdoing with the Sackler family. And these protagonists face potential negative consequences, right? Edward Snowden put his life on the line, quite frankly, to expose NSA surveillance. Nan Goldin didn't make any friends when she started protesting in every museum [where the Sackler family name hung, calling for its removal] – not the best thing to do if you're an artist and you're relying on these institutions.

US soldiers in Vietnam in a still from Cover-Up

I actually just realised that Cover-Up is the third feature-length film I've made about journalism. Because I did Risk – a film about Assange and WikiLeaks, which I think revolutionised journalism and lifted the veil on US foreign policy – and then Citizenfour. So obviously that's a preoccupation of mine: the role of adversarial journalism to expose wrongdoing in state power.

You mention in Cover-Up that you’ve been trying to make a film about Sy for 20 years, but he resisted. Why was he willing to collaborate now?

The original film I was proposing was something more observational and cinema-verité in style – to just follow him as he's doing his work. So that would include meeting sources – and even if I could anonymise, that was never going to fly for him. But after making All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, which also covers half a century and works with a lot of archival, I saw a different way of doing it. I realised there was so much archival coverage of Sy’s reporting that we could tell those stories with that sense of unfolding present-tense drama that I want in all of my films. I should say that once he agreed, he was all in, but it was still not a comfortable situation for him.

Yes – as you show in the film, he threatened to quit the project at one point. How did you handle that?

Tensions were definitely high. Most of his anger was coming towards me. We knew that Sy had quit a lot of other gigs – the New York Times, the AP, etcetera – so we knew it could be the end. But Mark went and talked to him that night, and it took about 24 hours, maybe a weekend, but it was fine after. He's somebody who says what he thinks in the moment. Which is great for us as filmmakers.

When did you have your political awakening?

I think being a citizen of the United States – I mean, it's a global empire. So I think I've always been aware of that power and the inequalities that go with that. As a kid, I went to a sort of a free, hippie school, so that was kind of part of a counterculture already.

Who is your current hero?

What I’ve always said is that I don't believe in heroes so much. People do heroic things, but people are people. But politically right now, it's obviously Zohran Mamdani. People talk about how there’s been a feeling of despair lately, so it's important to remember these kinds of victories. Him winning in New York is something nobody was predicting, and yet is the work of so many activists and thinkers who have paved the way for a moment like this to happen. And his mother is a great filmmaker, Mira Nair, whose work I’ve revered for decades. It’s just a very exciting thing that that's possible right in the centre of this country right now.

What would you say to someone who's struggling to feel optimistic in this moment?

Well, I'd go back to what’s happened in New York. One of the things we were trying to do with this film is make an argument that history is not inevitable, and that change does happen. We're creating history as we speak, by the choices that we make. And we can't forget that there are things that do turn the tide. Sy’s reporting on the Vietnam War and the My Lai massacre didn't end the war, but it certainly changed the public consciousness of what was really happening. We can’t succumb to the politics of despair. We all have an obligation not to abandon people, in Gaza or anywhere else in the world. We have an obligation to fight.

Is there a work of art that has inspired you recently?

Jafar Panahi’s film It Was Just an Accident – the fact that he was able to take something as dark as torture, and living under a regime that tortures people, and make it human and funny and provocative and thought-provoking. It asks the audience to think about their moral position in such a dark scenario. He inspires me as a filmmaker and as an intellectual in the world.

Where do you have your best ideas creatively?

I need to be hunkered down, not on the move. I have to be in a sort of more internal zone. Later, as filmmakers, we go through phases where we're making something and it's a very collaborative creative process, and then we’re in a more external mode.

If money or travel were no object, where would you choose to live?

That's a hard question right now, because I think places that I would have said before, I can't right now. Because I feel like that there's such a crackdown on freedom of expression, and we're seeing that around the world. I was going to say Berlin, because it's a place I went to when I had to leave the United States [to escape the attentions of the US security services]. But right now, it's not a place that is welcoming of free speech.

Before you became a filmmaker, your first career was as a chef. Are you still a keen cook?

I was really passionate about it in my teens and 20s. And then, you know, I really burned out. I still love to cook for friends and pull out the stops sometimes, but I'm not like a foodie. I don't go around to all the new restaurants and I'm not obsessed with following the new trends. It feels a bit in the past.

Is there something you always carry with you?

I'm trying to think of what I am willing to say! I always have a bit of an escape plan. Yeah, I guess that's what I carry with me. An escape plan.

Interview by Guy Lodge

Cover-Up is on Netflix from 26 December