Last Friday, 21 November, the former Ukip and Brexit party MEP and ex-leader of Reform UK in Wales, Nathan Gill, was sentenced to 10 and a half years in prison after admitting to taking up to £40,000 in bribes in exchange for pro-Russian interviews and speeches while serving as a member of the European Parliament (MEP).

I first encountered Gill’s name in January 2020. I was working in a Viennese library, following up on some of the material I had collected but had not used for my 2017 book exploring Russian influence on far right politics, Russia and the Western Far Right: Tango Noir. One of the under-explored links concerned Janusz Niedźwiecki, a Polish pro-Russian activist. Although he had come on to my radar in 2015, he was not significant enough at the time to appear in the 2017 book. However, by 2020 he had already been involved in several curious operations, and my interest grew.

My inquiry into Niedźwiecki’s activities brought to light his role in arranging

Gill’s travel to Ukraine, which in turn revealed Gill’s deeper involvement in pro-Kremlin networks. Initially, I summarised my early findings in a Facebook post and the comments to it.

The more I researched, the wider the pro-Kremlin European network I uncovered. Eventually, I decided to bring all my findings together and write a research report on Niedźwiecki, the people he worked for and the people he worked with. In the investigation I revealed, in particular, his work for the major Ukrainian pro-Russian politician Viktor Medvedchuk and several Russian politicians.

The Covid-19 pandemic slowed the writing process, and the report, The Rise and Fall of a Polish Agent of the Kremlin Influence: The Case of Janusz Niedźwiecki, was published only in November 2021.

In hindsight, I was glad that it had taken me longer to complete it. Polish security services arrested Niedźwiecki at the end of May 2021 on charges of espionage for Russia. Had I published the report before his arrest, it could have been linked to his apprehension in Poland – something I did not want to be associated with.

My report featured Gill and many other European politicians. Viktor Medvedchuk approached them with the help of people who worked for him: Ukrainian politician Oleh Voloshyn, Ukrainian journalist Nadia Borodi, also known as Nadia Sass, and Niedźwiecki. All three provided an organisational and logistical connection between Medvedchuk and a number of European politicians who would make various pro-Russian statements to the benefit of both Medvedchuk and Moscow. But Niedźwiecki also provided a connection between some of those European politicians and his Russian superiors.

Niedźwiecki was neither a sponsor of pro-Russian operations nor a pro-Russian ideologue: he was instead an organiser, a facilitator, a coordinator.

What I did not know at the time I wrote and published my report was the amount of money that Medvedchuk paid to Gill, and probably to some other European politicians who worked for him via Voloshyn or Niedźwiecki. The details of the financial relations between Voloshyn and Gill became public only earlier this year.

While hiking in Greece with a friend in November 2021, I had a rather lovely exchange on Facebook with Voloshyn under the post in which I announced the publication of my report (see the screenshot below, or follow the link to the post and all the comments).

But afterwards I generally forgot about Niedźwiecki and Gill. The Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 pushed my research interests in a different direction.

Voloshyn and Borodi/Sass fled Ukraine about two weeks before the full-scale invasion – they had probably been tipped off. Medvedchuk tried to flee as well, but was arrested by the Ukrainian security services, though he would later be sent to Russia in exchange for Ukrainian heroes captured by Russian forces during the invasion. (See the Nerve’s useful timeline here.) Once in Russia, Medvedchuk began cooperating with the Social Design Agency and funded the Voice of Europe – both of which would serve as tools of Russian political warfare against Europe.

I returned to Gill’s involvement in Russian influence networks in June 2024. I was shocked by the straightforwardly pro-Kremlin claims of Nigel Farage – the leader of Gill’s party, Reform UK – suggesting that the EU and Nato had provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The claims seemed suspicious to me, and I tweeted a thread briefly exploring the known links between Reform UK and (pro-)Russian influence operations. The initial post of the thread reached more than 2 million views.

Unexpectedly for me, in March 2025 Gill was charged in the UK with conspiring with Voloshyn to make paid pro-Russian statements in the European parliament on at least eight occasions between 2018 and 2020. Apparently, he had initially not planned to plead guilty, but eventually he did, which resulted in his sentencing to a lengthy prison term.

I presume Gill is not the only politician who took bribes, but he is the one who got caught

What really surprised me at that point was the length of time between the moment the British security services clearly knew about Gill’s involvement in pro-Russian activities and the moment when he was finally charged with bribery.

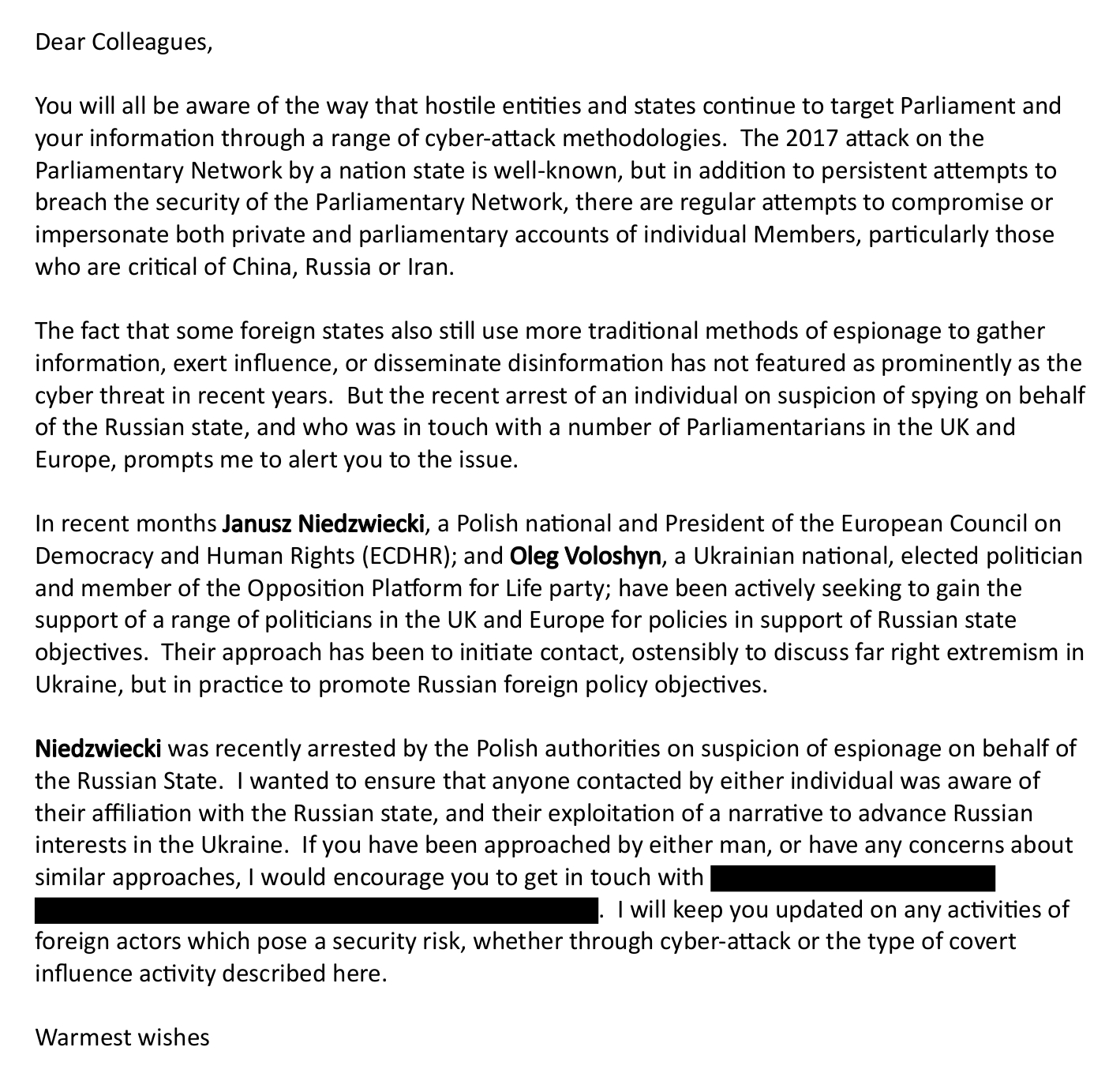

The latter moment is March 2025, while the former must be at least July 2021, when UK MPs received a letter from Lindsay Hoyle, speaker of the House of Commons, warning them of Niedźwiecki’s and Voloshyn’s efforts “to gain the support of a range of politicians in the UK and Europe for policies in support of Russian state objectives”. See the letter below.

What I gathered from rumours among my various contacts is that, following his arrest, Niedźwiecki cracked almost immediately and disclosed all his handlers and contacts to the Polish investigators. Since some of those individuals were non-Polish nationals, Poland’s security services duly shared their intelligence with their European counterparts, including in the UK.

That presumably led not only to the letter of caution sent to UK MPs in July 2021, but also to Gill’s arrest at Manchester Airport in September 2021. As the BBC reported, “his mobile phone was seized and evidence was found that … suggested he was in a professional relationship with Mr Voloshyn and had agreed to receive or accept monies in return for him performing activities as an MEP”.

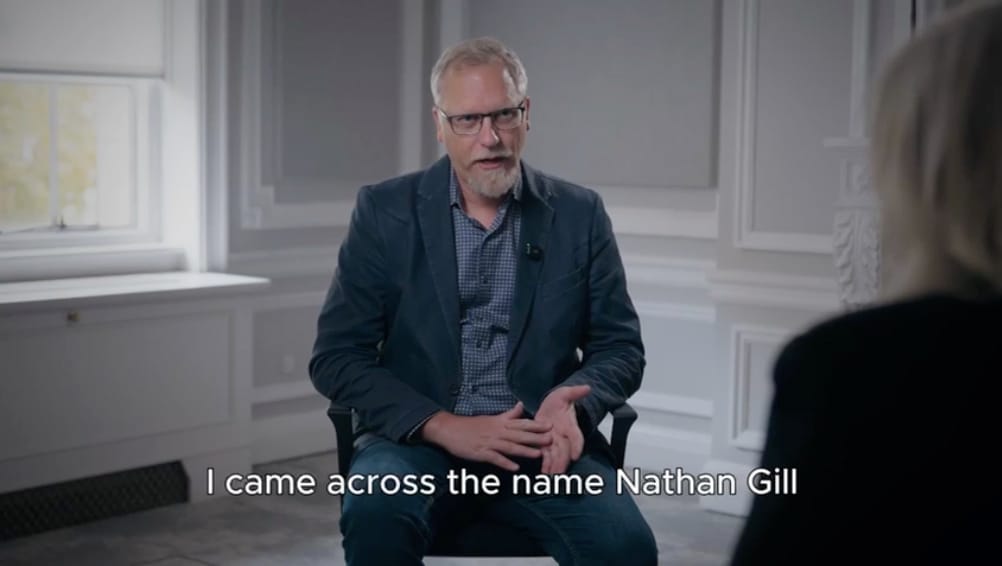

Commenting on Gill’s affair for the BBC documentary “Bribes, Lies and the British Politician”

This means that the UK investigators had all the evidence they needed to charge Gill with bribery for three and a half years. Why did they have to wait? Does this have something to do with the rise of Farage’s Reform UK?

As I said to Euronews the other day when commenting on Gill’s trial, his affair is only “the tip of the iceberg in a broader web of influence operations” – “I presume Gill is not the only politician who took bribes, but he is the one who got caught.”

Do the Polish security services who investigated Niedźwiecki’s activities have more names? Obviously. And haven’t my colleague and I revealed multiple pro-Russian influence operations involving dozens of European politicians? Indeed we have.

British police say they found nothing to link Farage to the Gill case but that investigations were ongoing into four further politicians or ex-politicians. Today – when Russia is waging a war against Europe – the notion that only Gill merits formal censure as a “bad apple” seems increasingly difficult to reconcile with the scale and persistence of the influence efforts already known and documented across the continent.

A version of this article first appeared on Anton Shekhovtsov’s Substack, Towers of Europa.